Signal Space#

Signal Space Concepts#

Inner Product of Complex Signals#

The inner product of two complex-valued signals, \( x_1(t) \) and \( x_2(t) \), is defined as:

Here, \( x_2^*(t) \) denotes the complex conjugate of \( x_2(t) \).

Orthogonal Signals#

Two signals are considered orthogonal if their inner product is zero:

Orthonormal Signals#

A set of \( m \) signals is orthonormal if:

The signals are mutually orthogonal.

Each signal has a norm of 1 (unit length).

Norm and Signal Energy#

The norm of a signal \( x(t) \) is defined as:

Here, \( \mathcal{E}_x \) represents the total energy of the signal \( x(t) \).

Linearly Independent Signals#

A set of \( m \) signals is considered linearly independent if no signal in the set can be expressed as a linear combination of the other signals.

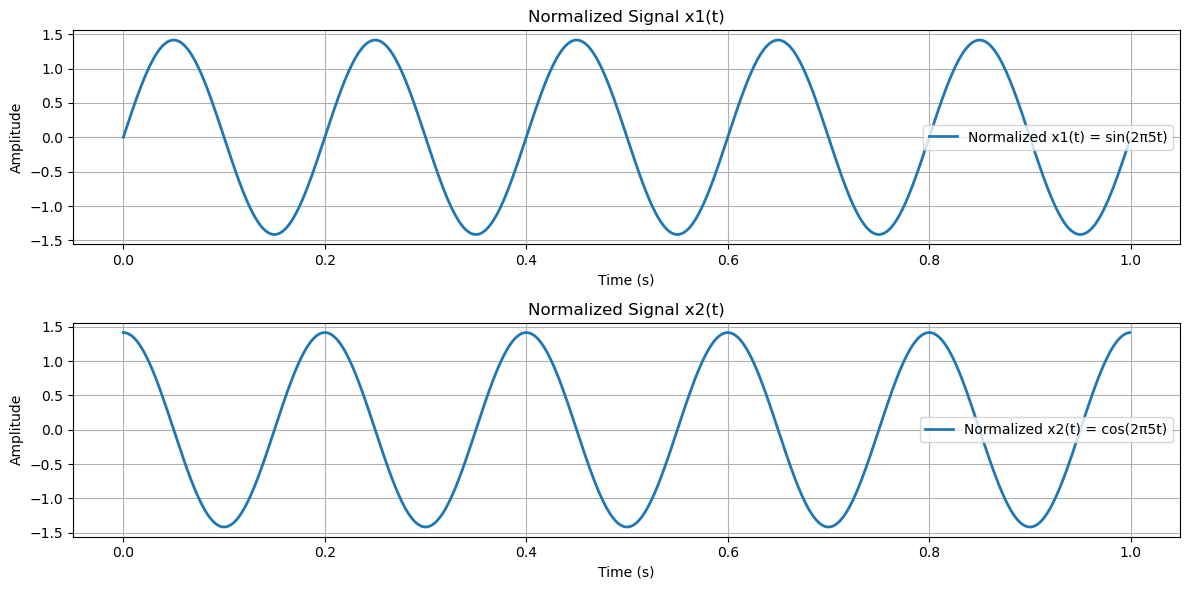

Python Example: Orthonormal Signals#

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define the simulation parameters

Fs = 1000 # Sampling frequency in Hz

T = 1 # Duration of the signal in seconds

t = np.arange(0, T, 1/Fs) # Time vector for one second worth of samples

# Define two signals

f = 5 # Common frequency

x1 = np.sin(2 * np.pi * f * t) # First signal: sine wave

x2 = np.cos(2 * np.pi * f * t) # Second signal: cosine wave (orthogonal to sine)

# Compute the norms (energy) of the signals

norm_x1 = np.sqrt(np.trapz(x1**2, t))

norm_x2 = np.sqrt(np.trapz(x2**2, t))

# Normalize the signals

x1_normalized = x1 / norm_x1

x2_normalized = x2 / norm_x2

# Compute the inner product of normalized signals

inner_product = np.trapz(x1_normalized * x2_normalized, t)

# Plot the signals

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

# Plot x1(t)

plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

plt.plot(t, x1_normalized, linewidth=2, label=f'Normalized x1(t) = sin(2π{f}t)')

plt.title('Normalized Signal x1(t)')

plt.xlabel('Time (s)')

plt.ylabel('Amplitude')

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

# Plot x2(t)

plt.subplot(2, 1, 2)

plt.plot(t, x2_normalized, linewidth=2, label=f'Normalized x2(t) = cos(2π{f}t)')

plt.title('Normalized Signal x2(t)')

plt.xlabel('Time (s)')

plt.ylabel('Amplitude')

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

# Show the plots

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Output the results

print(f"The norm of normalized x1(t) is: {np.sqrt(np.trapz(x1_normalized**2, t)):.6f}")

print(f"The norm of normalized x2(t) is: {np.sqrt(np.trapz(x2_normalized**2, t)):.6f}")

print(f"The inner product of the normalized signals is: {inner_product:.6f}")

# Check orthonormality

tolerance = 1e-3 # Tolerance for numerical precision

is_x1_normalized = abs(np.sqrt(np.trapz(x1_normalized**2, t)) - 1) < tolerance

is_x2_normalized = abs(np.sqrt(np.trapz(x2_normalized**2, t)) - 1) < tolerance

is_orthogonal = abs(inner_product) < tolerance

if is_x1_normalized and is_x2_normalized and is_orthogonal:

print("The signals are orthonormal.")

else:

print("The signals are not orthonormal.")

The norm of normalized x1(t) is: 1.000000

The norm of normalized x2(t) is: 1.000000

The inner product of the normalized signals is: 0.000031

The signals are orthonormal.

Some Important Inequalities#

Triangle Inequality#

For two signals \( x_1(t) \) and \( x_2(t) \), the triangle inequality states:

This inequality highlights that the norm of the sum of two signals is never greater than the sum of their individual norms.

Cauchy–Schwarz Inequality#

The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality is a fundamental result that applies to the inner product of two signals \( x_1(t) \) and \( x_2(t) \):

Equivalently, in integral form:

Equality holds in the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality if and only if \( x_2(t) = a x_1(t) \), where \( a \) is any complex scalar.

Orthogonal Expansions of Signals#

Vector Representation of Signals#

We can represent signal waveforms as vectors, demonstrating the equivalence between a signal waveform and its vector representation.

Let \( s(t) \) be a deterministic signal with finite energy:

Suppose there exists a set of orthonormal functions \( \{\phi_n(t)\}, n = 1, 2, ..., K \), such that:

Approximation of Signals#

The signal \( s(t) \) can be approximated as a weighted linear combination of these orthonormal functions:

Here, \( \{s_k\} \) are the coefficients representing the projection of \( s(t) \) onto the functions \( \{\phi_k(t)\} \).

The approximation error is given by:

Minimizing the Approximation Error#

The energy of the approximation error is:

To minimize \( \mathcal{E}_e \), the coefficients \( \{s_k\} \) are chosen such that \( \hat{s}(t) \) is the projection of \( s(t) \) onto the \( K \)-dimensional signal space spanned by \( \{\phi_k(t)\} \). In this case:

The minimum mean-square approximation error is:

This value is always nonnegative by definition.

Perfect Representation of Signals#

When the minimum mean-square error is zero (\( \mathcal{E}_{\text{min}} = 0 \)), we have:

Under this condition, \( s(t) \) can be expressed as:

This equality implies that \( s(t) \) is exactly represented by the series expansion, with no approximation error.

Complete Set of Orthonormal Functions#

Definition

A set of orthonormal functions \( \{\phi_n(t)\} \) is said to be complete if every finite-energy signal \( s(t) \) can be represented as:

with \( \mathcal{E}_{\text{min}} = 0 \).

Example: Trigonometric Fourier Series#

A Fourier series is a mathematical representation of a signal as a sum of sine and cosine functions. The idea is to decompose a signal \( s(t) \), defined over a finite interval \( [0, T] \), into its frequency components.

Signal Decomposition#

The signal \( s(t) \) can be expressed as:

where:

\( \cos \frac{2\pi kt}{T} \) and \( \sin \frac{2\pi kt}{T} \) are the basis functions representing periodic oscillations.

\( a_k \) and \( b_k \) are the Fourier coefficients that determine the contribution of each cosine and sine term.

Fourier Coefficients#

The Fourier coefficients \( a_k \) and \( b_k \) are derived to minimize the mean-square error, ensuring that the series closely approximates the original signal. They are calculated using:

Constant term (DC component):

\[ a_0 = \frac{1}{T} \int_{0}^{T} s(t) \, dt \]This represents the average (mean) value of the signal over \( [0, T] \).

Cosine coefficients:

\[ a_k = \frac{2}{T} \int_{0}^{T} s(t) \cos \frac{2\pi kt}{T} \, dt \quad \text{for } k = 1, 2, 3, \ldots \]These coefficients capture the contribution of cosine terms at different frequencies \( k/T \).

Sine coefficients:

\[ b_k = \frac{2}{T} \int_{0}^{T} s(t) \sin \frac{2\pi kt}{T} \, dt \quad \text{for } k = 1, 2, 3, \ldots \]These coefficients capture the contribution of sine terms at different frequencies \( k/T \).

Physical Interpretation

The trigonometric Fourier series reveals the frequency components (harmonics) of the signal.

\( a_0 \): Represents the average value of the signal.

\( a_k \): Amplitudes of the cosine components at different frequencies.

\( b_k \): Amplitudes of the sine components at different frequencies.

By combining these coefficients, we can reconstruct the original signal or analyze its frequency content.

Complete Basis Set

The functions:

form a complete orthonormal set over the interval \( [0, T] \), which means:

Any periodic signal (with the required properties) can be represented as a linear combination of these functions.

The approximation error vanishes as more terms are included, achieving zero mean-square error in the limit.

Python Simulation#

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Parameters

T = 1.0 # Duration (seconds)

fs = 1000 # Sampling rate (samples per second)

K = 100 # Number of harmonics

samples = int(fs * T) # Total number of samples

t = np.linspace(0, T, samples, endpoint=False) # Time vector

# Generate a square wave signal

square_wave = np.sign(np.sin(2 * np.pi * t / T))

# Compute Fourier coefficients

a0 = np.mean(square_wave) # DC component

ak = []

bk = []

for k in range(1, K + 1):

ak.append((2 / T) * np.sum(square_wave * np.cos(2 * np.pi * k * t / T)) / fs)

bk.append((2 / T) * np.sum(square_wave * np.sin(2 * np.pi * k * t / T)) / fs)

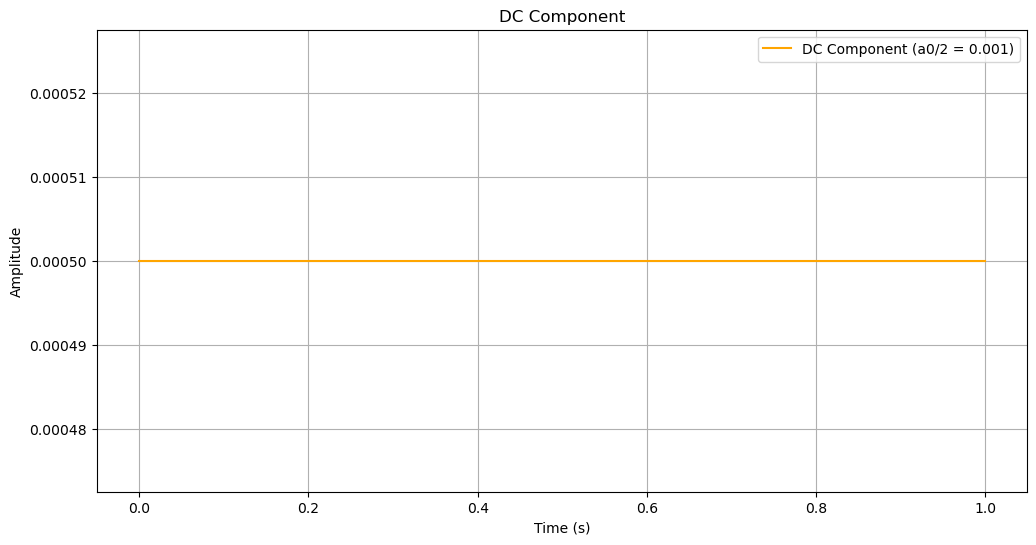

The Fourier series components#

DC Component: The constant offset (\( a_0/2 \)) is displayed in the first subplot.

# DC Component

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

plt.plot(t, np.full_like(t, a0 / 2), label=f"DC Component (a0/2 = {a0/2:.3f})", color='orange')

plt.xlabel("Time (s)")

plt.ylabel("Amplitude")

plt.title("DC Component")

plt.legend()

plt.grid()

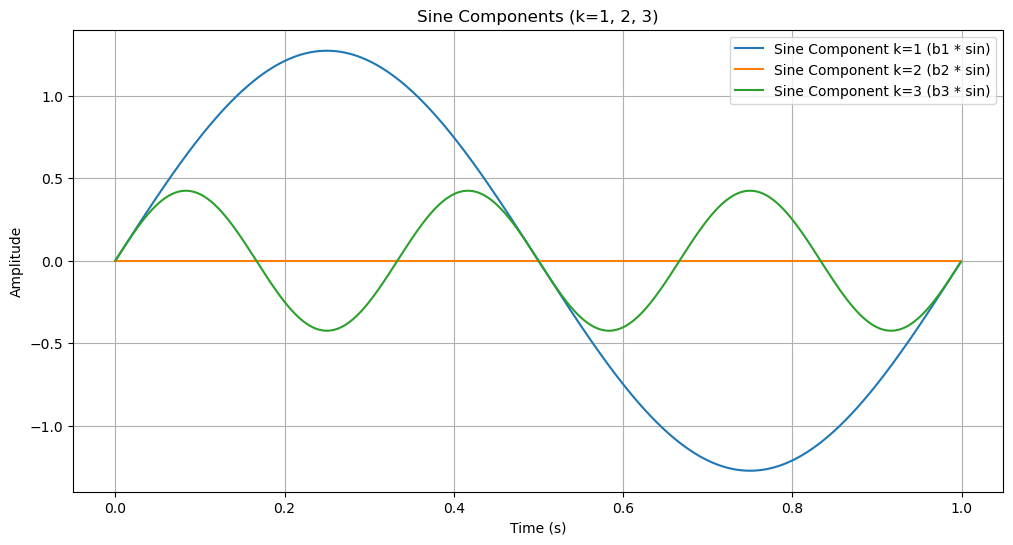

Sine Components: The sine terms (\( b_k \sin(2\pi kt / T) \)) for \( k = 1, 2, 3 \)

Note that, for \( b_k \):

For \( k = 2 \) (or any even \( k \)), the square wave alternates in such a way that the positive and negative parts of the sine wave cancel each other out perfectly, resulting in:

Generalized Consequence

\( b_k \) is zero for all even \( k \), so the sine components for even \( k \) do not contribute to the signal.

The observed “line” is likely just the \( y = 0 \) line, which corresponds to the sine component’s absence for \( k = 2 \).

# Sine Components for K = 1, 2, 3

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

for k in range(1, 4):

sine_component = bk[k - 1] * np.sin(2 * np.pi * k * t / T)

plt.plot(t, sine_component, label=f"Sine Component k={k} (b{k} * sin)")

plt.xlabel("Time (s)")

plt.ylabel("Amplitude")

plt.title("Sine Components (k=1, 2, 3)")

plt.legend()

plt.grid()

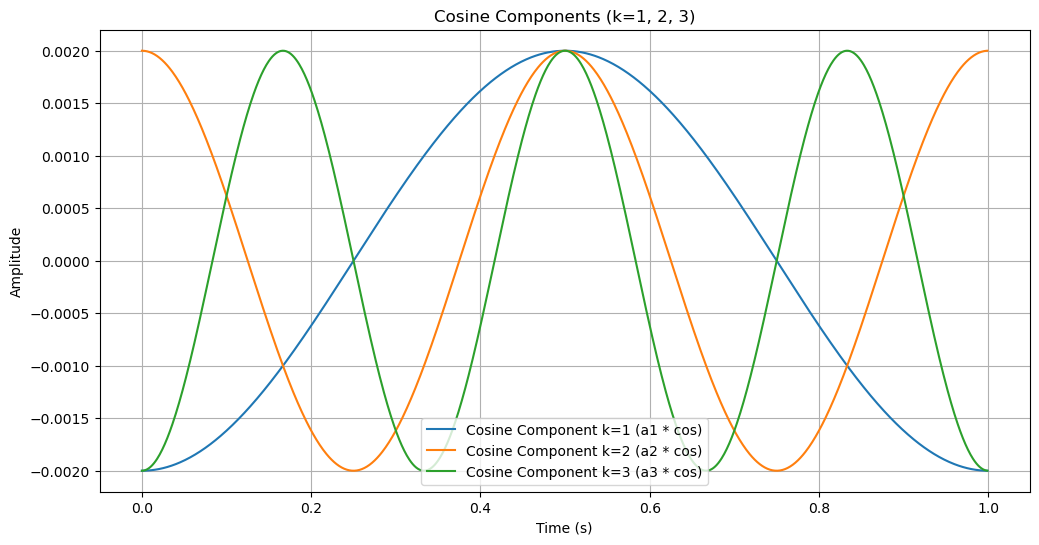

Cosine Components: The cosine terms (\( a_k \cos(2\pi kt / T) \)) for \( k = 1, 2, 3 \)

# Cosine Components for K = 1, 2, 3

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

for k in range(1, 4):

cosine_component = ak[k - 1] * np.cos(2 * np.pi * k * t / T)

plt.plot(t, cosine_component, label=f"Cosine Component k={k} (a{k} * cos)")

plt.xlabel("Time (s)")

plt.ylabel("Amplitude")

plt.title("Cosine Components (k=1, 2, 3)")

plt.legend()

plt.grid()

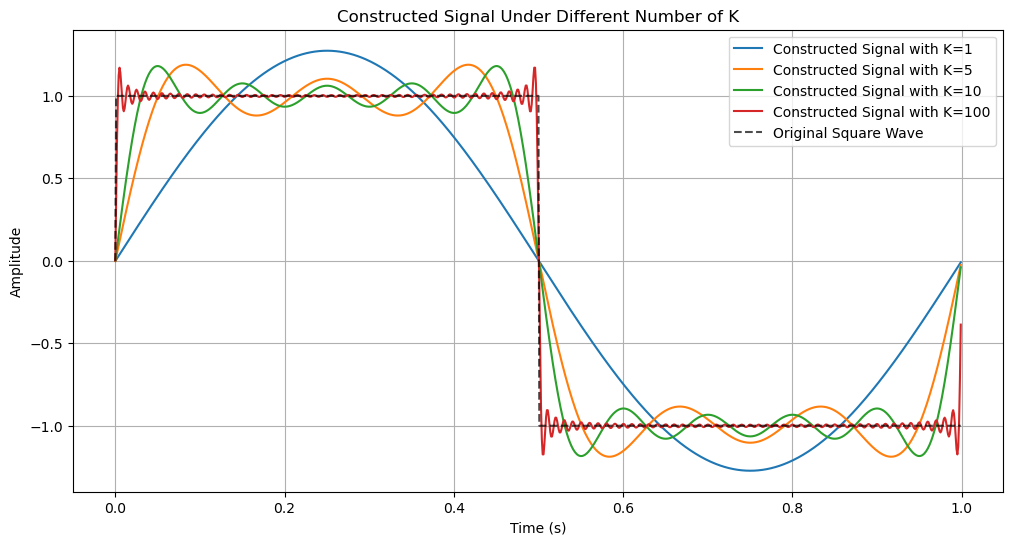

# Construct signal s(t) based on Fourier series

constructed_signals = []

for k_max in [1, 5, 10, K]: # Different numbers of harmonics

s_t = a0 / 2 # Initialize with DC component

for k in range(1, k_max + 1):

s_t += ak[k - 1] * np.cos(2 * np.pi * k * t / T) + bk[k - 1] * np.sin(2 * np.pi * k * t / T)

constructed_signals.append((k_max, s_t))

# Plot constructed signal for different numbers of K

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

for k_max, s_t in constructed_signals:

plt.plot(t, s_t, label=f"Constructed Signal with K={k_max}")

plt.plot(t, square_wave, 'k--', label="Original Square Wave", alpha=0.7)

plt.xlabel("Time (s)")

plt.ylabel("Amplitude")

plt.title("Constructed Signal Under Different Number of K")

plt.legend()

plt.grid()

plt.show()

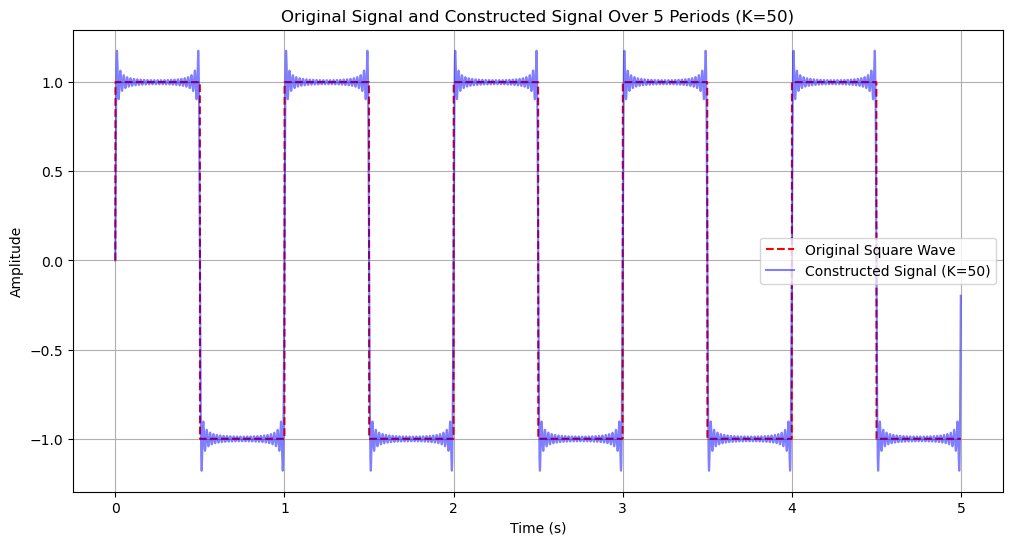

# Parameters for extended time range

periods = 5 # Number of periods to plot

t_extended = np.linspace(0, T * periods, samples * periods, endpoint=False) # Extended time vector

# Generate the extended square wave signal

square_wave_extended = np.sign(np.sin(2 * np.pi * t_extended / T))

# Construct the signal with K = 100 harmonics

K_max = 50

a0_extended = np.mean(square_wave) # DC component

s_t_extended = a0_extended / 2 # Start with the DC component

for k in range(1, K_max + 1):

s_t_extended += (

ak[k - 1] * np.cos(2 * np.pi * k * t_extended / T)

+ bk[k - 1] * np.sin(2 * np.pi * k * t_extended / T)

)

# Plot the original signal and the constructed signal

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

plt.plot(t_extended, square_wave_extended, label="Original Square Wave", linestyle="--", color="red")

plt.plot(t_extended, s_t_extended, label=f"Constructed Signal (K={K_max})", color="blue", alpha=0.5)

plt.xlabel("Time (s)")

plt.ylabel("Amplitude")

plt.title(f"Original Signal and Constructed Signal Over {periods} Periods (K={K_max})")

plt.legend()

plt.grid()

plt.show()